Showing posts with label Trees. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Trees. Show all posts

04 February 2014

06 December 2013

Friday Field Notes: Nature Journaling on a Brisk December Day

December 1, 2013

Norway Maple

Latin name: Acer platanoides

The Norway Maple originates from Europe and Western Asia and was introduced the the United States as an ornamental tree. The deciduous tree offers shade in the spring and summer and it is adapted to survive in adverse conditions, typical of Montana winters. It is believed that the first Norway Maples were brought to Missoula by Frank Worden, the founder of Missoula. Although a beautiful tree, the Norway Maple, with its dense canopies of foliage and allelopathic properties (a process in which its roots release a toxin into the ground) are known to displace native plant species.

27 October 2011

Philipsburg Area

Not much more than an hour outside of Missoula, you can escape to a little morsel of historical significance known as Philipsburg. It’s not too far along I-90 E, maybe 50 miles, after you wind past the forested areas of Beavertail and Bearmouth and emerge into a wide (and golden!) valley, that you turn off the interstate at Drummond and follow MT-1 S up the valley to the small town of less than a thousand.

At this time of year, the drive from Missoula to Drummond is spectacular with all the vibrant autumn colors--red maples, yellow larch, golden aspens--but the drive from Drummond to Philipsburg along the Pintar Scenic Route is phenomenal. I love slowing down and inspecting the ranches, looking at resting horses, wandering cattle, and ranchers leaning against the fence posts.

Philipsburg isn’t that big, but don’t let that deceive you into thinking that you could see it all from one place. I stayed two days and a night, and plan on going back because I didn’t see nearly everything that I wanted to (if you’re looking for a place to stay, I would recommend The Broadway Inn).

In town, there are numerous places to eat (Doe Brothers has stellar burgers and sweet potato fries) and a decidedly amazing candy store. The Sweet Palace is overwhelming! The fudge flavors are decadent and the truffles--oh, the truffles--are worth every bite. If you happen to get there when they are packaging salt water taffies and one of the taffies escapes unwrapped, they will give you it as a sample, and you will be struck with an inexplicable desire to buy more. Just a warning.

We went up to the cemetery on the hill and sought out the oldest headstones to get a sense of the beginnings of the city. There were so many sad stories contained in the collection of grave markings, stories of children lost over the years and all at once, fathers and mothers that died young or survived decades beyond their spouses and children, singular spouses left buried in the ground alone after their partners must have packed up all they had left and moved away.

We went on a wet weekend, but after the rain let up a little, we drove the narrow dirt road to Granite ghost town. It’s a road you’ll want a high clearance, 4WD vehicle for, but it’s worthwhile heading up there.

|

| Photo courtesy of Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks | http://visitmt.com/pictures/big/5179h.jpg |

|

| Photo courtesy of Sara Call |

The mine’s remaining structure is possibly the most impressive part of the area. It is massive, and only partially crumbling. Mica-studded granite sparkled throughout the rubble, brightened by the recent drizzle. The view from the mine’s perch was beautiful.  |

| Photos courtesy of Sara Call |

We made our way downstairs, and there sat all sorts of mining equipment and buildings models--the original sign from the general store, an assay office model, a miner’s cabin, and a massive lift (the original elevator) and hydraulic engine. The absolute most incredible part of the museum was the walk-in replica of a silver mine shaft, built by volunteers. It’s a wonderful piece of work.

There are a few other ghost towns around Philipsburg that you can also visit--Kirkville and Garnet, for example--and plenty of recreational activities to engage in around the area. Over the pass to the southeast is Georgetown Lake, and if you continue down MT-1 S you’ll come into Anaconda, another town of significance in our state’s history of mining.

Of course, there’s also Drummond, which is a character-filled town in and of itself... If you’re there on a Saturday, check out the Used Cow Lot!

Sources and links:

http://visitmt.com/categories/moreinfo.asp?IDRRecordID=6737&siteid=1

http://philipsburgmt.com/museum

http://www.drummondmontana.com/SurroundingArea.html

22 September 2011

Boxelder Bugs

The Boxelder bug (Boisea trivittata)

See also: Spotlight on Boxelder Tree, April 2010

I started typing this post about all of the autumn-time plants I’ve been seeing around Greenough Park, but I was interrupted when a boxelder bug crawled across the desk and onto the keyboard.

There has been an influx of them in the office. They are crawling on walls and bookshelves, down the stairs and up the doorways. I have seen half a dozen today alone. I have heard folks talking about them--and not everyone knows much about them.

Boxelder bugs are named for their love of boxelder trees. The bugs are attracted to the female boxelder trees, which are the seed-bearers that can be identified by their long slender blossoms that hang down and produce seeds similar to maple seedpods—the paired “whirlybirds.” Boxelder bugs will, to a lesser extent, also feed on maple, ash, and sometimes fruit trees. They use their ‘beak’—a proboscis—like a straw to suck juices out of plant material (predominately from seedpods), but they don’t seem to cause any damage to the trees.

I can see a female boxelder tree out the east window of the office, its seedpods hanging in dry clusters that will endure through the winter. The windowsill is crawling with bright boxelder bugs of all life stages, sunning in the mottled morning light.

|

| Sara C. 2011 |

The nymphs, or immature bugs, are bright red with round bottoms, which become more elongated and marked with black as they mature. The adults are a half-inch long, flat-topped and predominately grayish brown or black, with parallel red stripes on their thorax, a red abdomen, and red cross-markings on their wings. The bugs have big eyes and long, segmented antennae.

I don’t mind boxelder bugs; they don’t bite, or sting, or stink, or eat houseplants. They find ways into buildings, but don’t damage them. They just crawl around, looking for a nice place to sleep through the winter, and then come spring they go back outside to mate. They are considered pests simply because they are a plentiful, and therefore sort of a nuisance. (The boxelder bug at my desk is actually quite entertaining, and seems to enjoy following every cord from my computer and back.)

The boxelder bugs mark a change in seasons, a reminder that summer will come to an end. Other than that, they are absolutely harmless.

Though remember: don’t squish them, they’ll stain things.

References:

“Boxelder bugs and Conifer Seed/Leaffooted Bugs.” Montana Integrated Pest Management Center, 1997. http://ipm.montana.edu/YardGarden/docs/boxelderbugsconiferbugs-insect.htm

“Boxelder Bugs vs. Lady Bugs.” The Eclectic Scientist! June 23, 2010. http://angelasentomlabnotebook.blogspot.com/2010/06/boxelder-bugs-vs-lady-bugs.html

Swan, Lester and Charles Papp. The Common Insects of North America. Harper & Row Publishers, Inc: New York, 1972. p126.

See also: Spotlight on Boxelder Tree, April 2010

03 February 2011

Spotlight On...Redtwig Dogwood

Redtwig Dogwood

Cornaceae (Dogwood Family)

Quick ID:

Cornus sericea

Quick ID:

Redtwig dogwood is full of character throughout the year. In its leafless winter state, the conspicuous red branches set off a blaze of color against the snow.

Early spring brings dense, flat-topped clusters of creamy white flowers, which give way to pea-sized white berries in summer.

Cooler temperatures bring out purple and red anthocyanins in the leaves--the mass fall display of a dogwood thicket can really take your breath away. Look for this loosely spreading deciduous shrub, typically 6-12' high, growing in dense thickets in riparian areas and open forests.

The red twigs are tipped by a uniquely pointed terminal bud, and can be covered in lenticels on the old growth. Leaves are opposite (arranged in pairs along the stem), simple (not lobed), with entire (not serrated) margins that tend to be wavy and occasionally rimmed in purple.

Notice the way the veins sweep up toward the tip of the leaf. This is a great identifying feature that can be used to distinguish dogwood from the many other simple-leaved species out there (chokecherry, twinberry, huckleberry...I'm looking at you).

Range:

Very common throughout Canada and the northern US, south to Virginia on the east side and northern Mexico in the west. Look for it growing in the rich, moist soil of riparian areas and in forest openings, in conjunction with alder (Alnus spp.), willow (Salix spp.), cottonwood and aspen (Populus spp.), Wood's rose (Rosa woodsii), currants (Ribes spp.), Rocky Mountain maple (Acer glabrum) and horsetails (Equisetum spp.).

Very common throughout Canada and the northern US, south to Virginia on the east side and northern Mexico in the west. Look for it growing in the rich, moist soil of riparian areas and in forest openings, in conjunction with alder (Alnus spp.), willow (Salix spp.), cottonwood and aspen (Populus spp.), Wood's rose (Rosa woodsii), currants (Ribes spp.), Rocky Mountain maple (Acer glabrum) and horsetails (Equisetum spp.).

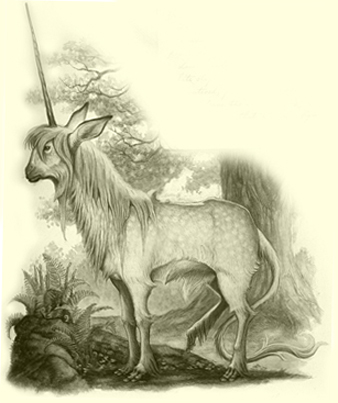

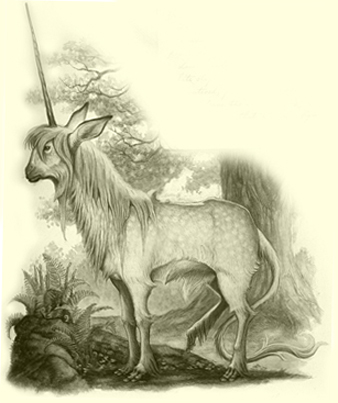

What's in a Name?

Cornus is the Latin word for horn (like a unicorn). The Romans called the dogwood "cornel", in reference to its wood, which is hard as the horn of a goat and useful for making a great many things. This is also a convenient way to remember the distinct leaf buds of redtwig dogwood, which are narrow and pointed like horns.

Cornus is the Latin word for horn (like a unicorn). The Romans called the dogwood "cornel", in reference to its wood, which is hard as the horn of a goat and useful for making a great many things. This is also a convenient way to remember the distinct leaf buds of redtwig dogwood, which are narrow and pointed like horns.

The species name sericea means silky, in reference to the fine hairs covering the leaves. The origin of the word "dogwood" itself is not totally settled. It may be a corruption of "dagwood", from the use of its hard wood in making dags (or daggers). Alternatively, there is some evidence that a concoction of English Cornus leaves was used to treat dog mange in 17th century herbology.

The species name sericea means silky, in reference to the fine hairs covering the leaves. The origin of the word "dogwood" itself is not totally settled. It may be a corruption of "dagwood", from the use of its hard wood in making dags (or daggers). Alternatively, there is some evidence that a concoction of English Cornus leaves was used to treat dog mange in 17th century herbology.

C. sericea is also commonly known as redosier dogwood. This may be confusing, since "osier" comes from the medieval term for willow (Salix sp.) In fact, the flexible young branches of C. sericea have long been used for basket weaving, much like the willows that grow in similar streamside thickets.

Cornus is the Latin word for horn (like a unicorn). The Romans called the dogwood "cornel", in reference to its wood, which is hard as the horn of a goat and useful for making a great many things. This is also a convenient way to remember the distinct leaf buds of redtwig dogwood, which are narrow and pointed like horns.

Cornus is the Latin word for horn (like a unicorn). The Romans called the dogwood "cornel", in reference to its wood, which is hard as the horn of a goat and useful for making a great many things. This is also a convenient way to remember the distinct leaf buds of redtwig dogwood, which are narrow and pointed like horns. The species name sericea means silky, in reference to the fine hairs covering the leaves. The origin of the word "dogwood" itself is not totally settled. It may be a corruption of "dagwood", from the use of its hard wood in making dags (or daggers). Alternatively, there is some evidence that a concoction of English Cornus leaves was used to treat dog mange in 17th century herbology.

The species name sericea means silky, in reference to the fine hairs covering the leaves. The origin of the word "dogwood" itself is not totally settled. It may be a corruption of "dagwood", from the use of its hard wood in making dags (or daggers). Alternatively, there is some evidence that a concoction of English Cornus leaves was used to treat dog mange in 17th century herbology.C. sericea is also commonly known as redosier dogwood. This may be confusing, since "osier" comes from the medieval term for willow (Salix sp.) In fact, the flexible young branches of C. sericea have long been used for basket weaving, much like the willows that grow in similar streamside thickets.

Tidbits:

Like most of our native plant species, dogwood has been, and continues to be, valued for its many benefits to humans. An extract made from the leaves, stems and inner bark can be used as an emetic for treating fevers and coughs (and a great many other ailments), and the inner bark scrapings have long been added to tobacco smoking mixtures. The red stems not only produce colorful weaving patterns, but can be used to make red, brown and black dyes.

The white berries, although tart and bitter, are not poisonous, and have been eaten by many people throughout history. The fruits are low in natural sugars, making them less attractive to wildlife and less likely to rot than other berries. Thus, dogwood fruit persists long into the winter, making it available when other food is not. These unlikely berries are a key food source of grizzly and black bears, and are also eaten by songbirds, waterfowl, cutthroat trout, mice and other animals. Beavers use the hard wood to build dams and lodges.

Thickets of dogwood are especially good habitat for little birds like the dusky flycatcher, orange-crowned warbler, Lincoln sparrow and the house finch pictured here. These thickets, often located along the river's edge, provide good places to rear young, with year-round security and food sources. Because of its thick root system, redtwig dogwood is also important for stabilizing these streambanks, particularly in places where stream channels are scoured by seasonal flooding.

Like most of our native plant species, dogwood has been, and continues to be, valued for its many benefits to humans. An extract made from the leaves, stems and inner bark can be used as an emetic for treating fevers and coughs (and a great many other ailments), and the inner bark scrapings have long been added to tobacco smoking mixtures. The red stems not only produce colorful weaving patterns, but can be used to make red, brown and black dyes.

The white berries, although tart and bitter, are not poisonous, and have been eaten by many people throughout history. The fruits are low in natural sugars, making them less attractive to wildlife and less likely to rot than other berries. Thus, dogwood fruit persists long into the winter, making it available when other food is not. These unlikely berries are a key food source of grizzly and black bears, and are also eaten by songbirds, waterfowl, cutthroat trout, mice and other animals. Beavers use the hard wood to build dams and lodges.

Thickets of dogwood are especially good habitat for little birds like the dusky flycatcher, orange-crowned warbler, Lincoln sparrow and the house finch pictured here. These thickets, often located along the river's edge, provide good places to rear young, with year-round security and food sources. Because of its thick root system, redtwig dogwood is also important for stabilizing these streambanks, particularly in places where stream channels are scoured by seasonal flooding.

Wild Gardening

Being a water-loving species, Cornus sericea is tolerant of moist soils and varying water tables. Once established, it also holds up well against drought. Research has shown that water-stressed plants actually have a higher tolerance to freezing cold temperatures. When dogwood senses the shortened days of oncoming winter, tissue changes occur that prevents the plant from taking up water and increases water lost through transpiration, so the tissue becomes dehydrated even when water is abundant. This interesting adaptation, along with C. sericea's somewhat complex ability to avoid freezing injury by having water freeze outside of its cells, should make it an incredibly cold-hardy choice for northern gardeners. BUT, remember the notorious cold snap of early October, 2009, when temperatures across Montana took a sudden dive into the single digits? Our 11-year-old redtwig dogwood--10' tall and strong as an ox, we thought--was the only significant plant we lost at the Nature Adventure Teaching Garden here in Missoula. Granted, all the plants at the NATG are dynamite no-fear natives that can take most anything the weather throws at them, so the garden's overwhelming hardiness came as no surprise. The loss of Big Red was a sad one, though.

Luckily, dogwood is easy to propagate by seed, layering or stem cuttings, and easy to establish in a range of soils. This is one shrub that will do fine in partial shade as well. And while the tender stems are preferred browse for deer, elk and moose, they're less enticing that many of the delectable non-native shrubs commonly planted as ornamentals. Aside from all the wildlife you'll be providing backyard habitat for, you'll also be enticing pollinators and butterflies with the fragrant white blossoms in spring (C. sericea is an important larval host for the Spring Azure (Celastrina ladon) butterfly. Overall, this is one of the best all-purpose native shrubs to plant for ease of care and year-round enjoyment.

Luckily, dogwood is easy to propagate by seed, layering or stem cuttings, and easy to establish in a range of soils. This is one shrub that will do fine in partial shade as well. And while the tender stems are preferred browse for deer, elk and moose, they're less enticing that many of the delectable non-native shrubs commonly planted as ornamentals. Aside from all the wildlife you'll be providing backyard habitat for, you'll also be enticing pollinators and butterflies with the fragrant white blossoms in spring (C. sericea is an important larval host for the Spring Azure (Celastrina ladon) butterfly. Overall, this is one of the best all-purpose native shrubs to plant for ease of care and year-round enjoyment.

Being a water-loving species, Cornus sericea is tolerant of moist soils and varying water tables. Once established, it also holds up well against drought. Research has shown that water-stressed plants actually have a higher tolerance to freezing cold temperatures. When dogwood senses the shortened days of oncoming winter, tissue changes occur that prevents the plant from taking up water and increases water lost through transpiration, so the tissue becomes dehydrated even when water is abundant. This interesting adaptation, along with C. sericea's somewhat complex ability to avoid freezing injury by having water freeze outside of its cells, should make it an incredibly cold-hardy choice for northern gardeners. BUT, remember the notorious cold snap of early October, 2009, when temperatures across Montana took a sudden dive into the single digits? Our 11-year-old redtwig dogwood--10' tall and strong as an ox, we thought--was the only significant plant we lost at the Nature Adventure Teaching Garden here in Missoula. Granted, all the plants at the NATG are dynamite no-fear natives that can take most anything the weather throws at them, so the garden's overwhelming hardiness came as no surprise. The loss of Big Red was a sad one, though.

Luckily, dogwood is easy to propagate by seed, layering or stem cuttings, and easy to establish in a range of soils. This is one shrub that will do fine in partial shade as well. And while the tender stems are preferred browse for deer, elk and moose, they're less enticing that many of the delectable non-native shrubs commonly planted as ornamentals. Aside from all the wildlife you'll be providing backyard habitat for, you'll also be enticing pollinators and butterflies with the fragrant white blossoms in spring (C. sericea is an important larval host for the Spring Azure (Celastrina ladon) butterfly. Overall, this is one of the best all-purpose native shrubs to plant for ease of care and year-round enjoyment.

Luckily, dogwood is easy to propagate by seed, layering or stem cuttings, and easy to establish in a range of soils. This is one shrub that will do fine in partial shade as well. And while the tender stems are preferred browse for deer, elk and moose, they're less enticing that many of the delectable non-native shrubs commonly planted as ornamentals. Aside from all the wildlife you'll be providing backyard habitat for, you'll also be enticing pollinators and butterflies with the fragrant white blossoms in spring (C. sericea is an important larval host for the Spring Azure (Celastrina ladon) butterfly. Overall, this is one of the best all-purpose native shrubs to plant for ease of care and year-round enjoyment.Thanks to Dave DeHetre, Bryant Olsen and Paul Alaback for some of the images used here.

Spotlight On... features Montana native plants that are currently on display in our natural areas. Have a plant that you'd like to see featured? Let us know!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)