On my ride into the Montana Natural History Center this morning there was one thing that was impossible not to think about: WIND. Struggling against a current of wind on an icy bike path is no cakewalk. Missoula doesn't get this windy too often, but just a handful of miles across the Continental Divide onto Montana's high plains, it's another story.

Most of Montana is occupied by rolling grasslands, once dominated by bison, pronghorn, and prairie dogs. Beautiful shortgrass prairie stretched from the flanks of the Rockies and moated the island ranges of the central and eastern parts of the state. The rich soils that sustained the plentiful life were also ideally suited for growing crops like wheat and alfalfa and stock grazing. A short time after the advent of white settlers, much of the prairie had been checkered with farms and fences, altering the pristine landscape into an anthropomorphized version of its former self.

|

| Looking out from Square Butte towards the Missouri River Breaks |

Weather, however, remains indifferent to our terrestrial tillings, not appearing to care about our comfort or chapped faces.

Wind has played an important role in Montana's history, particularly on the eastern slope of the Rockies. From harnessing wind for energy production, to dispersal of seeds and pollen for various plants, wind, despite its indifference, is critical for life on the prairie.

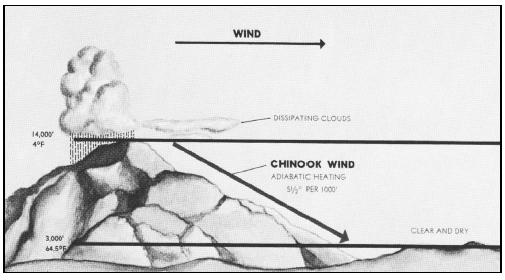

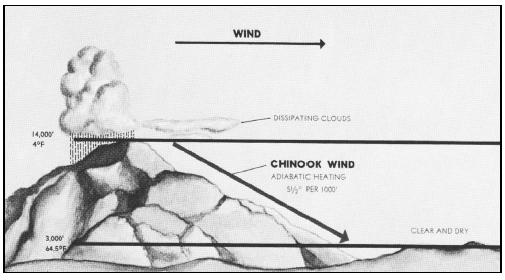

Chinook winds have certainly made their mark on Montana history. A Chinook wind a is warm, dry air mass that rips down the east slope of high mountains and warms the plains it crosses. Chinooks form from westerly humid cells of air from the Pacific that dump their moisture on the west sides of mountain ranges (the great and mighty Rockies in our case), then warm

adiabatically on their way back down the eastern side. The Chinook winds reach temperatures up to 60 degrees F and tear across that landscape at speeds up to 100 mph, melting and

sublimating snow in their wake.

|

| http://www.weatherexplained.com/images/walm_01_img0191.jpg |

These winds are most common and severe from Cutbank to Helena, Montana. The high, steep eastern slopes of Glacier and the Bob Marshall and Scapegoat Wildernesses warm more quickly. The greatest temperature change in a 24-hour period in the U.S. was due to a Chinook wind, and occurred in Loma, Montana. The temperature went from -54 to 49 F, a 103-degree change! It is plain to see that ranchers would have relied on these remarkable weather events to make it through the unforgiving winters that punctuate every year in central Montana.

|

| Waiting for a Chinook by Charlie Russell |

As I bike back home today against that not-so-warm wind coming out of the mouth of Hellgate Canyon, I'll be dreaming of warm, dry Chinooks on the prairie.