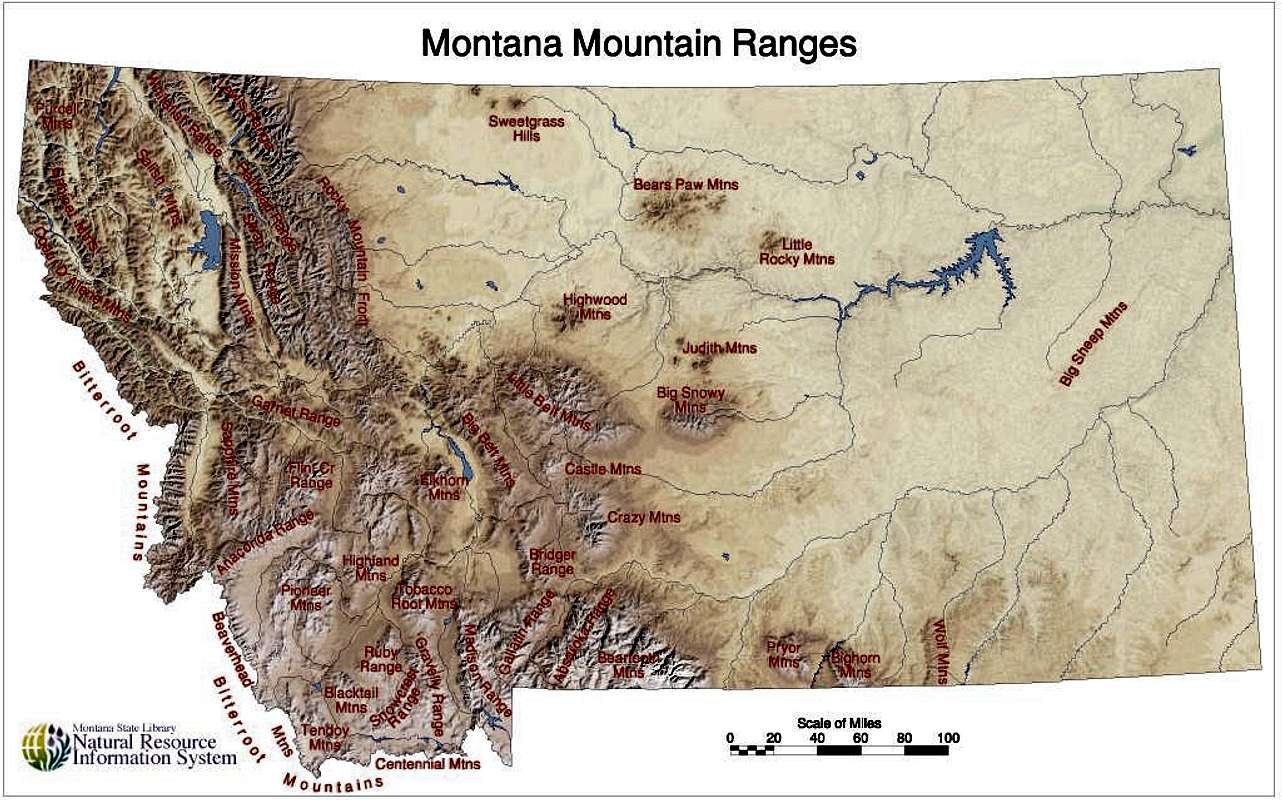

Not much more than an hour outside of Missoula, you can escape to a little morsel of historical significance known as Philipsburg. It’s not too far along I-90 E, maybe 50 miles, after you wind past the forested areas of Beavertail and Bearmouth and emerge into a wide (and golden!) valley, that you turn off the interstate at Drummond and follow MT-1 S up the valley to the small town of less than a thousand.

At this time of year, the drive from Missoula to Drummond is spectacular with all the vibrant autumn colors--red maples, yellow larch, golden aspens--but the drive from Drummond to Philipsburg along the Pintar Scenic Route is phenomenal. I love slowing down and inspecting the ranches, looking at resting horses, wandering cattle, and ranchers leaning against the fence posts.

Philipsburg isn’t that big, but don’t let that deceive you into thinking that you could see it all from one place. I stayed two days and a night, and plan on going back because I didn’t see nearly everything that I wanted to (if you’re looking for a place to stay, I would recommend The Broadway Inn).

In town, there are numerous places to eat (Doe Brothers has stellar burgers and sweet potato fries) and a decidedly amazing candy store. The Sweet Palace is overwhelming! The fudge flavors are decadent and the truffles--oh, the truffles--are worth every bite. If you happen to get there when they are packaging salt water taffies and one of the taffies escapes unwrapped, they will give you it as a sample, and you will be struck with an inexplicable desire to buy more. Just a warning.

We went up to the cemetery on the hill and sought out the oldest headstones to get a sense of the beginnings of the city. There were so many sad stories contained in the collection of grave markings, stories of children lost over the years and all at once, fathers and mothers that died young or survived decades beyond their spouses and children, singular spouses left buried in the ground alone after their partners must have packed up all they had left and moved away.

We went on a wet weekend, but after the rain let up a little, we drove the narrow dirt road to Granite ghost town. It’s a road you’ll want a high clearance, 4WD vehicle for, but it’s worthwhile heading up there.

|

| Photo courtesy of Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks | http://visitmt.com/pictures/big/5179h.jpg |

It’s difficult to believe that 3,000 people once lived where a few ruins now cling to the mountainside. We wandered along the Granite Ghost Walk and sought out foundations, most of which were broken up by tree roots and frost weathering. It’s amazing to think that the buildings in this area were built by hand, from the huge stones set in near-perfect walls to brick arches to giant steel towers. It’s amazing to think that the trees and vegetation have filled in so much in the past hundred and some years.

|

| Photo courtesy of Sara Call |

The mine’s remaining structure is possibly the most impressive part of the area. It is massive, and only partially crumbling. Mica-studded granite sparkled throughout the rubble, brightened by the recent drizzle. The view from the mine’s perch was beautiful.

|

| Photos courtesy of Sara Call |

On our second day of exploring, we made an appointment with a volunteer at the Granite County Museum and Cultural Center. Esther, a spunky older lady with lots of knowledge and hard work behind her, chatted with us but didn’t prepare us for how much we would get for our $3 admission fee. The upstairs portion of the exhibit included models, clothing, saddles, and cattle brands from way back to the 1870’s. Photos and descriptions of local ghost towns lined the walls, and an extensive mineral and rock collection filled an entire corner of a room.

We made our way downstairs, and there sat all sorts of mining equipment and buildings models--the original sign from the general store, an assay office model, a miner’s cabin, and a massive lift (the original elevator) and hydraulic engine. The absolute most incredible part of the museum was the walk-in replica of a silver mine shaft, built by volunteers. It’s a wonderful piece of work.

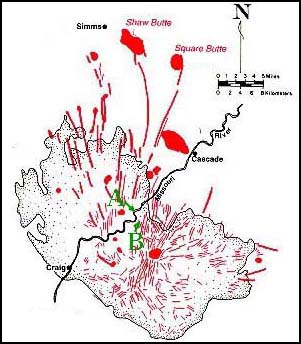

There are a few other ghost towns around Philipsburg that you can also visit--Kirkville and Garnet, for example--and plenty of recreational activities to engage in around the area. Over the pass to the southeast is Georgetown Lake, and if you continue down MT-1 S you’ll come into Anaconda, another town of significance in our state’s history of mining.

Of course, there’s also Drummond, which is a character-filled town in and of itself... If you’re there on a Saturday, check out the Used Cow Lot!

Sources and links:

http://visitmt.com/categories/moreinfo.asp?IDRRecordID=6737&siteid=1

http://philipsburgmt.com/museum

http://www.drummondmontana.com/SurroundingArea.html